Difference between revisions of "Geneve wait state generation"

m |

|||

| Line 159: | Line 159: | ||

The problem has become worse with the higher performance of the Geneve. This may mean that programs that worked well with the TI may fail to run on the Geneve because of VDP overruns. For this reason, wait states may be inserted for video operations. | The problem has become worse with the higher performance of the Geneve. This may mean that programs that worked well with the TI may fail to run on the Geneve because of VDP overruns. For this reason, wait states may be inserted for video operations. | ||

The Geneve generates two "kinds" of wait states when accessing the VDP. The first kind has been explained above; the VDP is an external device and therefore gets one wait state per default, and two when extra wait states are selected. After the access, however, the Gate Array pulls down the READY line for another 14 cycles when the [[Geneve_CRU_definitions|CRU bit]] for video wait states is set (address 0x0032 or bit 25 when the base address is 0x0000). | |||

Interestingly, the long wait state period starts after the access, which causes this very access to terminate, and then to start the period for the next command. This means that those wait states are completely ineffective in the following case: | |||

// Assume workspace at F000 | |||

F040 MOVB @VDPRD,R3 | |||

F044 NOP | |||

F046 DEC R1 | |||

F048 JNE F040 | |||

The instruction at address F040 requires 5 cycles: get MOVB @,R3, get the source address, read from the source address, 1 WS for this external access, write to register 3. Then the next command is read (NOP) which is in the on-chip RAM (check the addresses). For that reason, the READY pin is ignored, which has been pulled low in the meantime. NOP takes three cycles, as does DEC R1, still ignoring the low READY. JNE also takes three cycles. If R1 is not 0, we jump back, and the command is executed again. | |||

Obviously, the counter is now reset, because we measure that the command again takes only 5 cycles, despite the fact that the 14 WS from last iteration are not yet over. | |||

However, if we add an access to SRAM, we will notice a delay: | |||

// Assume workspace at F000 | |||

F040 MOVB @VDPRD,R3 * 5 cycles | |||

F044 MOVB @SRAM,R4 * 15 cycles (4 cycles + 11 WS) | |||

F046 DEC R1 * 3 cycles | |||

F048 JNE F040 * 3 cycles | |||

But we only get 11 WS, not 14. This is reasonable if we remember that the access to SRAM does not occur immediately after the VDP access but after writing to R3 and getting the next command. This can be shown more easily in the following way: | |||

{| class="waitstate" | |||

! 0 !! 1 !! 2 !! 3 !! 4 !! 5 !! 6 !! 7 !! 8 !! 9 !! 10 !! 11 !! 12 !! 13 !! 14 !! 15 !! 16 !! 17 !! 18 !! 19 !! 20 | |||

|- | |||

| MOVB @,R3 | |||

| VDPRD | |||

| wait | |||

| < *VDPRD | |||

| > R3 | |||

|- | |||

| MOVB @,R4 | |||

| SRAM | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| w | |||

| < *SRAM | |||

| > R3 | |||

|- | |||

| DEC R1 | |||

| < R1 | |||

| > R1 | |||

|- | |||

| JNE | |||

| < PC | |||

| > PC | |||

|- | |||

|} | |||

Revision as of 13:36, 20 October 2011

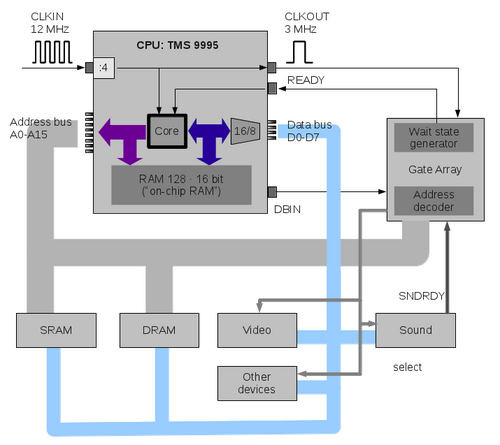

Architecture

This is a simplified schematic of the addressing mechanism in the Geneve.

The CPU, the TMS 9995, contains an own set of memory locations at addresses >F000 to >F0FB and the remaining 4 bytes at the end of the address space, that is, >FFFC to >FFFF (which are the NMI branch vector). The internal memory locations are directly connected to the 16 bit data bus, so we should say these are 128 words of 16 bit each.

All other memory locations are outside of the CPU, and the 16 bit data transfers are converted to a sequence of two 8 bit data transfers. This is quite similar to the mechanism used in the TI-99/4A, with the exception that the TI send the odd address byte first, then the even address, and the TMS 9995 starts with the even address, followed by the odd address.

Wait states can only be created outside of the CPU; there is no way of creating wait states within the CPU (possibly also no need). There is a special PIN called READY which is used for wait state creation.

Instead, we have an external wait state generation. The gate array circuit is used to create wait states in certain situations. When a wait state shall appear, the READY line of the CPU must be pulled down (cleared).

One wait state has the exact duration of one cycle which is 333.3 nanoseconds. Three millions of them last for one second.

Apart from the permanent wait state, the CPU itself does not create any wait state. This should be considered when only internal accesses are done: If code is running within the internal CPU RAM, wait states have no effect. They have only effect for external memory accesses.

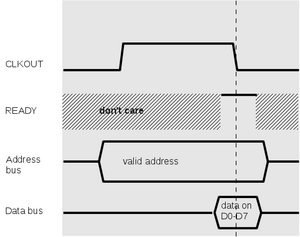

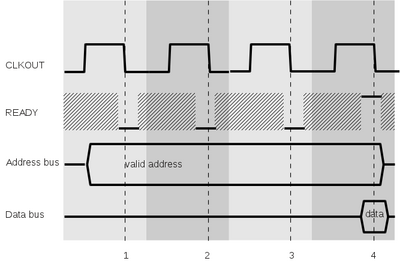

Timing diagrams

Some diagrams may help to understand the concept of wait states on the Geneve. I picked some of the lines, but there are some more, also important ones. If you are interested in the exact set of signal lines please see the TMS9995 specification. For now, we only discuss waitstate generation.

Cycles are defined as starting from halfway of the low level, containing the whole high level, and ending at half of the time of the next down level. If we use one letter as one quarter of a cycle, it would read as LHHL. In the diagrams, each cycle has an own backdrop which differs from the next.

This is the timing diagram for reading from external memory. A read operation starts with the address lines (A0-A15) being set to some value. For example, when the CPU wants to read from >1000, A3 is set to 1 while the remaining address lines are set to 0.

Next we expect that the device (like RAM, video, etc.) puts the value of the given address on the data bus. Depending on the device, the requested data may be available after some delay time, or the lines may be unstable until that time has passed. The CPU waits for the falling edge of the CLKOUT signal. At that point it first checks the READY line, and if it is high as shown here, the data lines are sampled, and the memory read access is complete. After that the program counter is increased and the next access may start.

Notice that the READY line may have any value (0 or 1) at other times; we symbolize this with the hashed stripe.

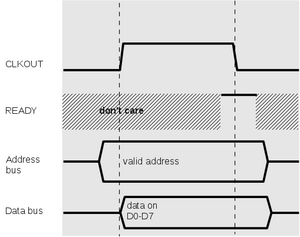

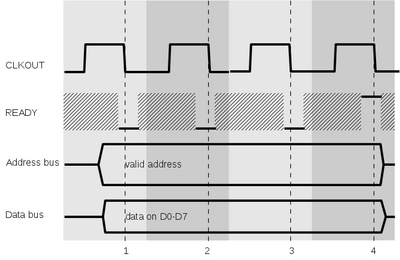

For writing the diagram looks a bit different, but still familiar. Again we omit some lines like WE line (write enable) for now. Different to reading, the writing process requires that the data bus be set shortly after the address is set. This is clear, since we must assume that the addressed device immediately fetches the values once the address is set. The CPU has no influence on the behavior of the device.

The external device may require some more time before the processing can continue; in this case it may lower the READY line; the CPU will test the line on the next falling CLKOUT edge. When it is high, as shown here, the memory write is complete, and the CPU continues with the next cycle, advancing the program counter. Remember that the CPU ignores the READY line when the memory access was directed to the internal memory locations, so in that case, the memory access is always complete at the end of the cycle.

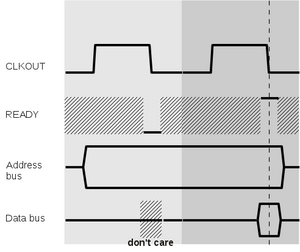

Now we have a look at the situation when a wait state is inserted. Here, a read operation is delayed by one cycle; this is typically the case when the Geneve uses its DRAM.

The memory read access starts as above, but at the first CLKOUT falling edge, the READY line is low. Now if this read access is actually an external access (and not to the on-chip RAM), the CPU skips the sampling of the data bus and waits for another falling CLKOUT edge. At that point we are at the same situation as above, and the access is complete.

What happens if we have multiple wait states? On the left side we can see a read access; as expected, the CPU loops until the READY line is high, and at that point it reads the values from the data bus. When writing, the CPU again attempts to assign the values shortly after the rising edge of CLKOUT, which is also used by the external device as the moment after which data may be safely read. The external device pulls down the READY line for this and another two cycles. This causes the CPU to loop until it finds a high READY level.

From this we learn two important points for creating wait states:

- When reading, wait states should occur before the actual read operation. Once the READY line is high, the memory access is considered as complete by the CPU, and it will advance its program counter and continue with the current or the next command. If the READY line is lowered afterwards it will only affect the following processing.

- When writing, wait states must start with the first cycle and continue for the desired times, with the last cycle showing a high READY line. Once the READY line is high, the operation is complete.

Byte accesses and word accesses

The TMS9995 is a 16 bit CPU, and as such all commands occupy two, four, or six bytes (including the arguments). Two bytes are also called a word (for 16 bit machines).

The on-chip RAM is word-addressable. That is, all words and each operand can be read in one memory cycle. If only one byte needs to be read or written, the RAM can also be addressed by byte locations (which is an important difference to the TMS9900 operation and considerably increases the efficiency of the TMS9995).

However, when we use external memory, all commands and arguments must be read by two cycles each, since the data bus only has 8 lines outside of the CPU. This has a visible impact on performance, especially when wait states are used.

Example:

F000: MOV R1,@>F080

If the workspace is located in the on-chip RAM (e.g. at >F040) we get 4 cycles for this operation:

- read the instruction MOV R1,@... : 1 cycle

- read the contents of R1 (>F042, >F043): 1 cycle

- read the target argument (F080): 1 cycle

- write the contents to the target address: 1 cycle

which makes 4 cycles or 1.332 µs execution time.

If the workspace is located in DRAM instead, we get more cycles:

- read the instruction MOV R1,@... : 1 cycle

- read the contents of >F042: 1 wait state, 1 read cycle = 2 cycles

- read the contents of >F043: 1 wait state, 1 read cycle = 2 cycles

- read the target argument (F080): 1 cycle

- write the contents to the target address: 1 cycle

together 7 cycles or 2.331 µs.

Now for the slowest option, assuming that we have a DRAM at the location 3000:

3000: MOV @>3800,@>3802

- read the instruction MOV @,@ (first byte): 2 cycles

- read the instruction MOV @,@ (second byte): 2 cycles

- read the source operand (first byte): 2 cycles

- read the source operand (second byte): 2 cycles

- read the byte at 3800: 2 cycles

- read the byte at 3801: 2 cycles

- read the target operand (first byte): 2 cycles

- read the target operand (second byte): 2 cycles

- write the byte at 3802: 2 cycles

- write the byte at 3803: 2 cycles

together 20 cycles (6.66 µs).

Wait states per device type

On-chip RAM

This one cannot have any wait state, as we stated above, since the access occurs within the CPU, and the READY pin is ignored. Reading and writing is the same case.

SRAM access

SRAM accesses by default do not create wait states. That means that the only slowdown compared to the chip-internal memory comes from the fact that we need two accesses to external memory where one access would have sufficed internally. This may indeed become expensive:

INC R1

requires 3 cycles when the code and the workspace is in the on-chip RAM (get the instruction, read the contents of R1 and increase them, write the contents of R1). As you see, the TMS9995 is able to do pipelining, which can be seen here. The instruction actually only requires three cycles although we have four activities. This is another reason why the Geneve is so much faster than the TI, although both use the same clock speed.

If the workspace were in SRAM, we would need 5 cycles (two cycles each for reading and writing to R1). If the command were in SRAM also, we get 6 cycles.

When the CRU bit at address 1EFE is set to 0, the Gate array produces extra waitstates. In the case of SRAM accesses, two waitstates are inserted before the read access. For write accesses, two waitstates are included, starting with the access. This means that the above command when running in SRAM and with workspace in SRAM requires 18 cycles instead of 6.

DRAM access

For each DRAM access, the gate array creates by default 1 wait state. That means that for word accesses (like CLR or MOV), two wait states will be created. Again with the example

INC R1

running in DRAM with R1 in DRAM as well, we get 6 memory accesses with 2 cycles each, that is, 12 cycles.

With extra waitstates, the Gate array adds another waitstate for reading and writing. This means that SRAM and DRAM accesses operate at exactly the same speed.

Devices

For external bus accesses (to the peripheral box), waitstates are used just as if accessing DRAM. That is, in the normal case, one WS is inserted for reading and writing. With extra waitstates, two WS are inserted.

These waitstates apply to

- the video processor (apart from the "background" waitstates; see below)

- the memory map registers

- the keyboard interface

- the clock chip

- the sound chip (also see below)

- the GROM simulator in the Gate Array (since the GROMs are stored in DRAM)

- the cards in the Peripheral Expansion Box.

Video operation

As known from the TI-99/4A, accesses to the Video Display Processor must be properly timed, since the VDP does not catch up with the higher speed of the CPU. In fact, using a dedicated video processor turns the TI and Geneve into a multiprocessor machine, in contrast to other home computers of that time.

As we have independent processors, a synchronization line is usually required to avoid access operations at times when the other processor is not ready. However, there is no such line in the TI and Geneve. Texas Instruments recommends to insert commands to take some time before the next access, like NOPs or SWPB.

When bytes are written in a too fast succession, some of them may be lost; when reading, the value may not reflect the current video RAM contents. Setting the address may also fail when writing too quickly. The V9938 video processor of the Geneve offers its command completion status in a registered that can be queried from a program, but there is no synchronization by signal lines.

The problem has become worse with the higher performance of the Geneve. This may mean that programs that worked well with the TI may fail to run on the Geneve because of VDP overruns. For this reason, wait states may be inserted for video operations.

The Geneve generates two "kinds" of wait states when accessing the VDP. The first kind has been explained above; the VDP is an external device and therefore gets one wait state per default, and two when extra wait states are selected. After the access, however, the Gate Array pulls down the READY line for another 14 cycles when the CRU bit for video wait states is set (address 0x0032 or bit 25 when the base address is 0x0000).

Interestingly, the long wait state period starts after the access, which causes this very access to terminate, and then to start the period for the next command. This means that those wait states are completely ineffective in the following case:

// Assume workspace at F000 F040 MOVB @VDPRD,R3 F044 NOP F046 DEC R1 F048 JNE F040

The instruction at address F040 requires 5 cycles: get MOVB @,R3, get the source address, read from the source address, 1 WS for this external access, write to register 3. Then the next command is read (NOP) which is in the on-chip RAM (check the addresses). For that reason, the READY pin is ignored, which has been pulled low in the meantime. NOP takes three cycles, as does DEC R1, still ignoring the low READY. JNE also takes three cycles. If R1 is not 0, we jump back, and the command is executed again.

Obviously, the counter is now reset, because we measure that the command again takes only 5 cycles, despite the fact that the 14 WS from last iteration are not yet over.

However, if we add an access to SRAM, we will notice a delay:

// Assume workspace at F000 F040 MOVB @VDPRD,R3 * 5 cycles F044 MOVB @SRAM,R4 * 15 cycles (4 cycles + 11 WS) F046 DEC R1 * 3 cycles F048 JNE F040 * 3 cycles

But we only get 11 WS, not 14. This is reasonable if we remember that the access to SRAM does not occur immediately after the VDP access but after writing to R3 and getting the next command. This can be shown more easily in the following way:

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOVB @,R3 | VDPRD | wait | < *VDPRD | > R3 | ||||||||||||||||

| MOVB @,R4 | SRAM | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | w | < *SRAM | > R3 | |||||

| DEC R1 | < R1 | > R1 | ||||||||||||||||||

| JNE | < PC | > PC |

Sound chip

TODO

Automatic wait state generation

Within the Geneve, wait states can be generated to slow down operation for keeping timing constraints. The TMS 9995 CPU can create wait states itself on every external memory access by a certain hardware initialization (READY high with RESET going from low to high). This is not used in the Geneve as those wait states cannot be turned off.