Difference between revisions of "GeneveOS Memory Management Functions"

m (→Virtual pages) |

|||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

Accordingly, physical addresses range from '''000000''' to '''1FFFFF'''. The TMS 9995, however, cannot use physical addresses since they do not match the 16 bit width of the address bus. The Geneve architecture includes a [[Geneve paged memory organization | memory mapper]] which is used to map the logical address space of the CPU to the physical address space. So when the CPU accesses the logical address A080 the mapper determines which physical address this corresponds with. For instance, if the mapper contains the value 2C for execution page 5, the logical address A080 maps to physical address 058080. | Accordingly, physical addresses range from '''000000''' to '''1FFFFF'''. The TMS 9995, however, cannot use physical addresses since they do not match the 16 bit width of the address bus. The Geneve architecture includes a [[Geneve paged memory organization | memory mapper]] which is used to map the logical address space of the CPU to the physical address space. So when the CPU accesses the logical address A080 the mapper determines which physical address this corresponds with. For instance, if the mapper contains the value 2C for execution page 5, the logical address A080 maps to physical address 058080. | ||

=== Virtual pages === | === Virtual (local) pages === | ||

In principle, multitasking is possible whenever we have means of passing control between independent applications. This can be done explicitly (by ''yielding'') or timer-controlled. For multiple tasks we have to take care that each task gets a part of the global memory area exclusively for itself. | In principle, multitasking is possible whenever we have means of passing control between independent applications. This can be done explicitly (by ''yielding'') or timer-controlled. For multiple tasks we have to take care that each task gets a part of the global memory area exclusively for itself. | ||

Revision as of 00:46, 13 November 2011

Memory management in MDOS is available via XOP 7. In the MDOS sources the relevant files are manage2s and manage2t.

Fast RAM is all memory with 0 wait states (SRAM), while Slow RAM is 1 wait state RAM, offered by the DRAM chips. The on-chip RAM is not considered here as it is not manageable by MDOS. The 256 bytes of on-chip RAM are always visible in the logical address area F000-F0FB and FFFC-FFFF. Any page that is mapped to the E000-FFFF area will be overwritten by operations in that area; this must be considered when using the E000-FFFF area.

Two classes of memory management functions are available: XOPs for user tasks, and XOPs exclusively used by the operating system.

Introduction and terminology

As it was common with TI application programming, buffers were usually placed statically in the program, that is, a portion of memory (like 256 bytes) was reserved in the program code to be used for storing data. Assembly language offers the BSS and BES directives for this purpose. This is not recommended when the buffer is very big, like 12 KiB, since that space will bloat the program code that must be loaded on application start. It is impossible for even larger buffer spaces like 100 KiB. In that cases, dynamic allocation is the typical solution also known from other systems.

The Geneve offers 512 KiB of slow RAM and another 32 KiB of fast RAM. Starting from MDOS 2.5, the fast RAM must be expanded to 64 KiB. Obviously, this memory can only be effectively used with the help of memory management functions.

Logical address space and execution pages

The logical address space are the addresses as seen from the CPU. The Geneve uses a 16-bit address bus which means that the logical address space is 64 KiB large. The CPU itself is not capable of addressing more memory, which is a limitation for application design. It essentially means that a transparent access to more than 64 KiB is impossible. The CPU is not capable of representing addresses outside this area.

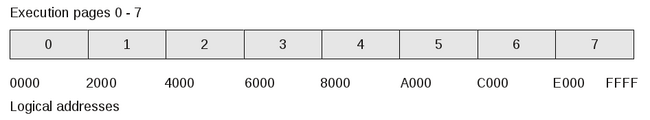

The connection between execution pages and the logical addresses can be seen here:

Execution pages are associated to logical addresses in a fixed way; the logical address allows to easily calculate the execution page: The first three bits determine the execution page. The remaining 13 bits are the 8 KiB memory space within this execution page.

Physical address space and physical pages

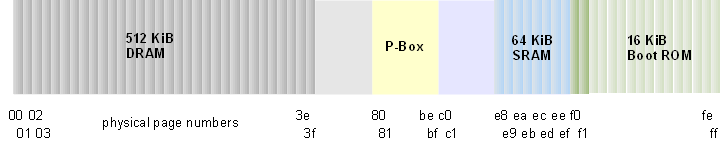

The physical address space comprises the complete memory area of the Geneve from the hardware viewpoint. There is no consideration of allocation to tasks. The physical address space consists of 256 pages of 8 KiB each, together 2 MiB.

The first 64 pages are the DRAM area (the slow RAM); from page number E8 to EF we find 8 pages of fast SRAM. The original configuration of the Geneve only included 32 KiB of SRAM, but in most cases this was expanded to 64 KiB. From page F0 to FF we find the Boot ROM; there is room for 128 KiB, but only 16 KiB are actually used, since the page address is not completely decoded in this area: All even pages are the same page, and all odd pages are the same page as well.

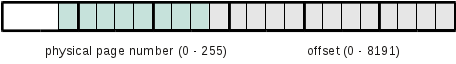

Physical addresses can be represented as shown here:

Accordingly, physical addresses range from 000000 to 1FFFFF. The TMS 9995, however, cannot use physical addresses since they do not match the 16 bit width of the address bus. The Geneve architecture includes a memory mapper which is used to map the logical address space of the CPU to the physical address space. So when the CPU accesses the logical address A080 the mapper determines which physical address this corresponds with. For instance, if the mapper contains the value 2C for execution page 5, the logical address A080 maps to physical address 058080.

Virtual (local) pages

In principle, multitasking is possible whenever we have means of passing control between independent applications. This can be done explicitly (by yielding) or timer-controlled. For multiple tasks we have to take care that each task gets a part of the global memory area exclusively for itself.

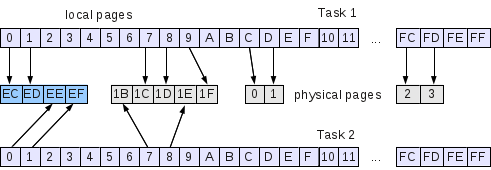

This handling requires that the access to memory be "virtualized"; we do not allow a direct access to the physical memory but map "virtual addresses" to a physical addresses. This indirection has an important advantage in multitasking systems: Every process may run as if it was the only one in the system, as the page it refers to with the number 0 is not really the physical page 0 but the one that was assigned to the task as taking the "role" of page 0; the same holds for all other pages.

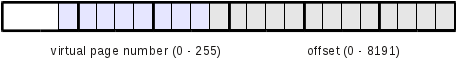

The illustration shows how the "virtual pages" of the task are mapped to physical pages. We see that a task may use up to 256 pages, covering the complete physical space. This is an untypical, extreme case, though. A task should only make use of those pages it really needs. This means that many, in fact most of the virtual pages are unassigned.

In this example, another task could be loaded in the system, but that task will not make use of the physical pages EF, EE, ED, 1C, ... 2, 3. It will be allocated some pages from the rest of the "pool" of free physical pages.

When a task is done the allocated memory should be returned to the system; otherwise the pool of pages dries up, and no more tasks can be loaded and run (a so-called memory hole).

Now how do virtual addresses look like? - Just like physical addresses:

In fact the virtual page number just needs to be mapped to the physical page number if that virtual page has got such an associated physical page.

As said above, the CPU can only work with logical addresses, not with physical addresses. This is also true for virtual addresses. We can, however, write programs that need to care for the proper paging, like the XOPs presented here.

Virtual address spaces in other architectures

Virtual memory and its management in PC architectures refers to the mechanism by which a part of the logical address is interpreted as an index in a page table (or a cascaded page table). The page table contains pointers to physical memory and also to space on a mass storage, allowing for swapping pages in and out. The Geneve memory organization is similar to this concept as a pointer into a table is translated to a prefix into the physical address space.

However, and this is a notable difference, there is no support for virtual addresses in the TMS 9995. We may, of course, write applications that take care of memory mapping, but this is a pure software solution. The XOPs as shown below, and also other XOPs like those for file access, provide such a software implementation of virtual addressing.

PC architectures with the Intel 8086 had an address bus of 20 bits (1 MiB address space), the Intel 80286 had an address bus width of 24 bit which already allowed for 16 MiB address space. Modern PCs have at least a 32-bit wide address. A process may thus make use of a maximum of 232 bytes or 4 GiB. Here the address space is (or better was) larger than the amount of memory in the system. (Now you know why you might want to change to a 64-bit architecture.)

With our Geneve, however, the address space is smaller than the amount of available memory, and we neither have any kind of segment registers as in the 8086. This means that we will never have a similarly simple, expandable memory model as known from the PC world. Any kind of memory paging must be handled on the software level.

The concept as presented here as some similarities with the EMS technology on PCs which was dropped with the availability of the 80386 and newer processors featuring the protected mode that allowed programs to make use of the virtual memory management.

User-task XOPs

User-task XOPs are available for use in application programs.

Available memory pages

Opcode: 0

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0000) | Error code (always 0) |

| R1 | Number of free pages | |

| R2 | Number of fast free pages | |

| R3 | Total number of pages in system |

Allocate pages

Opcode: 1

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0001) | Error code (0, 1, 7, 8) |

| R1 | Number of pages | Number of pages actually fetched to complete map as required |

| R2 | Local page address | Number of fast pages fetched |

| R3 | Speed flag (if not 0, only fast) |

This function is used to claim pages from the set of unassigned physical pages. This is particularly useful when the application requires more than just small buffers.

Free pages

Opcode: 2

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0002) | Error code (0, 2) |

| R1 | Number of pages | |

| R2 | Local page address |

Error code 2 is returned when the local page address (R2) is 0; page 0 cannot be freed in this way.

Map local page at excution page

Opcode: 3

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0003) | Error code (-, 2, 3) |

| R1 | Local page number | |

| R2 | Execution page number |

The local page numbers are the IDs of the allocated memory pages. The task contains a linked list of pointers to these local pages; the last list element points to 0. The list of pages is not sorted, so the search for a special local page may require to traverse the complete list.

Error code 2 is returned when the local page number or the execution page number is 0.

Error code 3 is returned when the execution page number is higher than 7 or the list does not contain an entry with the given local page number.

Get address map

Opcode: 4

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0004) | Error code (-, 8) |

| R1 | Pointer to buffer | Count of pages reported |

| R2 | Buffer size |

On return of the call, the memory locations pointed to by R1 contain a sequence of physical page numbers that have been allocated. R1 contains the length of this sequence.

Error code 8 is returned when the buffer is too small to hold the list of numbers of allocated pages.

Opcode: 5

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0005) | Error code |

| R1 | Number of pages to declare as shared | |

| R2 | Local page address | |

| R3 | Type to be assigned to shared pages |

Opcode: 6

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0006) | Error code |

| R1 | Type |

Also have to check their current execution map

Opcode: 7

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0007) | Error code |

| R1 | Type | |

| R2 | Local page number for start of shared area |

Opcode: 8

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0008) | Error code |

| R1 | Type | Number of pages in shared group |

Privileged XOPs (only available for operating system)

Release task

Opcode: 9

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (0009) |

Task header at >8000

Page get

Opcode: 10

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (000A) | Error code |

| R1 | Page number to get (if high byte not 0, get first available) | Pointer to node |

| R2 | Speed flag (if not 0, only fast) | Page number from node |

Add page to free pages in system

Opcode: 11

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (000B) | Error code (if no free nodes available) |

| R1 | Page number | Pointer to node |

Add a node to the list of free nodes

Opcode: 12

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (000C) | Error code (always 0000) |

| R1 | Pointer to node |

Link a node to the specified node

Opcode: 13

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (000D) | Error code (always 0000) |

| R1 | Pointer to node | |

| R2 | Pointer to node to link to |

Get address map (system)

Opcode: 14

| Input | Output | |

|---|---|---|

| R0 | Opcode (000E) | Count of valid pages |

Error codes

| Code | Meaning |

|---|---|

| 00 | No error |

| 01 | Not enough free pages |

| 02 | Can't remap execution page zero |

| 03 | No page at local address |

| 04 | user area not large enough for list |

| 05 | Shared type already defined |

| 06 | Shared type doesn't exist |

| 07 | Can't overlay shared and private memory |

| 08 | Out of table space |